A Spectre is Haunting Hollywood: The History of Howard Hughes and HUAC - Part I

Kyle Gagnon is a third year UNLV film student and Hannah Tran is a senior at UNLV majoring in film and English. Both are student assistants working on the "Inventing Hollywood: Preserving and Providing Access to the Papers of Renegade Genius Howard Hughes" joint project sponsored by the UNLV Libraries Special Collections and Archives and the UNLV Department of Film, which is funded by a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

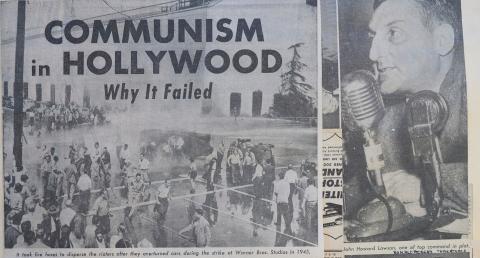

Our work as processing assistants on the Howard Hughes Motion Pictures Papers (HHMPP) as part of the “Inventing Hollywood" project has allowed us to discover a number of fascinating items collected by Howard Hughes and his staff relating to the investigations of communism within Hollywood by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). These materials include magazines, binders of newspaper clippings, and legal documents related to blacklisted screenwriter Paul Jarrico. The collection provides a deeper understanding of the effect of HUAC, the Hollywood response toward possible communist influence, and Hughes’ attitude toward communism. These materials inspired us to research this time period and Hughes’ involvement in anti-Communist activities.

Following World War II, the fear of fascism gave way with the fall of the Nazis. The United States’ former ally, the Soviet Union, quickly replaced the Nazis as the enemy and provoked the “red scare”, or the new fear of communism. This fear became embedded in society, and the effect it has on modern American political thinking is still visible today. Those sympathetic or friendly to communists were referred to as “fellow travelers,” and those registered with the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), or thought to be registered, were investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Founded in 1938, HUAC called upon those suspected of having communist ties to testify in Congress, and prosecuted those who refused to talk or name other communists by charging them with contempt.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, HUAC set its sights on Hollywood and those working within it. To HUAC, Hollywood represented an especially unique threat to the American public. Had Hollywood been infiltrated by communist agents seeking to produce propaganda for the purpose of inspiring an uprising in the United States? Or was HUAC doing more harm than good by inspiring panic in the media itself and ruining the lives of those it investigated in the process? Regardless of the intentions of either HUAC or the alleged communists, one thing was certain: Howard Hughes was no fan of communism. However, the reasons behind Hughes’ anti-communist sentiments may have been less patriotic and more practical.

In 1948, the aviation tycoon and business magnate purchased the struggling studio, RKO Radio Pictures (RKO). Hughes, who was known for his demanding and unpredictable behavior during his time as an independent movie producer, was now in control of a Big Five film studio and his time at RKO would be no different. Within weeks, production at RKO began to dwindle as Hughes terminated approximately 700 employees and investigated those who remained for possible communist connections.

But it was Paul Jarrico, a screenwriter and producer who was writing one of RKO’s latest films, The Las Vegas Story (1952), who was perhaps most actively targeted by Hughes’ supposed patriotism. In 1951, after refusing to answer questions regarding his communist connections before HUAC, RKO fired Jarrico under claims that he violated the morals clause within his contract. Jarrico denied the allegations and used the argument of Hughes’ defense of actor Robert Mitchum, whose recent arrest for marijuana possession RKO overlooked, to defend himself. Jarrico’s work on The Las Vegas Story was immediately scrapped and a new script prepared in its place.

Once the film premiered, however, Jarrico argued that enough of his contributions were used and demanded he receive on-screen credit. What followed was a drawn-out battle between Hughes, who argued Jarrico’s statements were not true and that the dispute was not related to labor, and the Screen Writers Guild (SWG), who argued that it was, in fact, a labor issue and that it was their duty to determine credits, not the studio’s. Then, in the first suit from a studio against an unfriendly witness, Hughes asked the Superior Court to relieve RKO from any duty to credit Jarrico. In retaliation, Jarrico filed a $350,000 damage suit against RKO to which Hughes responded that he should “just answer the question.” The HHMPP collection contains a large number of Hughes’ personal collection of newspaper clippings depicting this drawn-out legal dispute.

The dispute between Hughes and the SWG was far from over as each exchanged several heated letters that were widely publicized in Hollywood's entertainment press. The SWG’s letters defended its membership and pleaded for various forms of support from other guilds, unions, and the public. Hughes’ letters pressured them for an answer as to whether they planned to strike and sought to further discredit them by writing “Gentlemen: you are paid writers of fiction, and the strongest portions of your letter are fiction in its most brilliant form.”

Both the SWG and RKO were facing internal conflict as well as some members of the SWG claimed that the Guild, under the leadership of then-president Mary McCall, was not doing enough to take a firm stance against communist influence. Hughes, on the other hand, created an intense screening process to remove workers with supposedly disagreeable politics and laid off an additional 100 employees due to the financial strain of the legal battle. But outside the realm of the film industry, Hughes’ dedicated attack on “communist influence” was awarded with high praise and commendations, most notably from the American Legion, the American Veterans organization, and Richard Nixon.

Stay tuned for the next installment of this compelling story in the coming weeks.

Works Cited

Aberdeen, J. A. “California Pictures: Howard Hughes & Preston Sturges.” California Pictures:Howard Hughes and Preston Sturges, Hollywood Renegades Archive, 2005, www.cobbles.com/simpp_archive/howard_hughes.htm.

“The Chronicles of Hollywood's Mad Director: Howard Hughes - Page 24 of 52.” History by Day, 13 Sept. 2020, www.historybyday.com/human-stories/hollywoods-mad-director-howard-hughes/24.html.

“Dare Ya.” Fortnight, 14 Apr. 1952, pp. 6–7.

“Guild May Ask Court Force Hughes to Act in Jarrico Case.” Los Angeles Herald & Express, 4 Apr. 1952, p. 6.

“Nixon Lauds Stand On Screen Writer.” Los Angeles Herald & Express, 3 Apr. 1952, p. 12.

Simkin, John. “Paul Jarrico.” Spartacus Educational, Spartacus Educational, Sept. 1997, spartacus-educational.com/USAjarrico.htm.

“State Legion Pledges Aid to Hughes in Red Fight .” Citizen-News, 2 Apr. 1952, p. 5.

“SWG Board Ducks RKO Strike.” The Hollywood Reporter, 31 Mar. 1952, pp. 1–4.

“Veteran's Group Honors Hughes for Red Stand.” Los Angeles Times, 27 Apr. 1952, p. 3.