The glory days of Spanish conquest of the New World were long past when Herrera wrote his history almost two generations later. Spain itself was in fact in decline and would continue so for a long time. But Spain in the 16th century was the great European power and certainly to the other Europeans especially protestant Europeans, the great evil empire. This was Spain of the Counter Reformation and the Inquisition, the Spain which had annexed Portugal, and occupied Italy and the Netherlands . This was Spain of the Black Legend as it came to be known, of Spanish domination, arrogance and cruelty

The Black legend derived in part from the Spanish themselves who wrote about their experience in the New World with a naïve egotism that was easily turned by European translators into the dark deeds of evil and cruel colonial slavers and tyrants. Accounts of Spain in the New World flooded the European book trade and fueled anti Spanish feelings. It was to counter this propaganda that Phillip II suppressed many Spanish accounts and appointed Herrera as the official historian to produce a history that would silence Spain 's enemies.

Herrera succeeded in writing a great history that has survived. It was the basis for several modern historical works in the 19th century. It is still extensively cited as a source, because Herrera included – and often plagiarized -- accounts that no longer exist. In this Herrera preserved much history that would otherwise be lost.

We see that history differently now of course, thanks to the rich culture and self-conscious historical traditions that developed in the former Spanish colonies but that earlier history remains part of our history and our European cultural baggage.

larger image 438KBOne of the most vitriolic and famous earlier accounts was written by Bartolomé Las Casas, a Dominican friar and later Bishop of Chiapas in Mexico entitled a Brief Relation of the Destruction of the West Indies, first printed in 1552. Having spent much of his life in Mexico he wrote flaming, bitter denunciations of Spanish rule, filled with lurid first-hand accounts and depictions of the barbaric cruelties inflicted upon the Indians. It was translated into the various European languages (including this edition in English). Las Casas, ironically, did more than anyone else to establish the “Black Legend” of Spanish cruelty which so inflamed violent anti-Spanish feelings in a Europe which felt besieged by Spanish troops and by Spanish ships on the high seas and the English Channel. Las Casas engaged in lively and sometimes heated debates with Spanish intellectuals and officials and his works were eventually suppressed in Spain . Antonio de Herrera, however, had access to his manuscripts, including that of a much larger unpublished work, Historia De Las Indias, which Herrera incorporated into his own history, softening the diatribes but preserving much of Las Casas' eyewitness accounts. Herrera used the fact that Las Casas was allowed to publish his reports and dedicated them to the Spanish emperor as evidence of the Christian paternalism of the Spanish royalty towards her colonies. The New Laws of 1542, which were promulgated in large measure to mitigate the worst of colonial abuses of the native Indians, were a reaction to the revelations and uproar caused by Las Casas' published attacks and by his own single-minded determination to influence and reform royal policy.

larger image 254KB

Francisco Lopez de Gomara, 1511-1564. The conquest of the Weast India Ann Arbor, University Microfilms, 1966

Born at Seville, Spain, in 1510 de Gomara studied at the University of Alcala, was ordained priest, made a journey to Rome, and upon his return in 1540, entered the service of Hernándo Cortés as private and domestic chaplain. Like Antonio de Herrera, Lopez de Gomara never visited the New World . But with the information given him by Cortez and others who had returned from the New World he wrote his "Hispania Victrix; First and Second Parts of the General History of the Indies, with the whole discovery and notable things that have happened since they were acquired until the year 1551, with the conquest of Mexico and New Spain", a work published at Saragossa in the year 1552, and quickly translated into French and Italian. Lopes de Gomara died in Seville in 1564.

Similarly de Gómara Gomara's history, with its explicit recounting of Cortez's cruel and ruthless treatment of the native people and rulers, was being translated and used as grist for anti-Spanish propaganda in Italy, France and the Netherlands. Philip II in 1553, ordered all the copies of his work that could be found to be gathered in and imposed a penalty of 200,000 maraveds on anyone who should reprint it. The "Verdadera historia de la Conquista de Nueva España" (True History of the Conquest of New Spain) of Bernal Diaz del Castillo, a companion of Hernando Cortes, was written to refute Gómara.

larger image 443KBBernardino de Sahagún, d.1590. Conquest of New Spain : 1585 revision; reproductions of the Boston Public Library Manuscript and Carlos Maria de Bustamante 1840 edition; translated by Howard F. Cline; edited with an introduction and notes by S.L. Cline Salt Lake City : University of Utah Press, 1989

Bernardino Sahagun was a Spanish missionary, born in Sahagun, Leon, late in the 15th century. He studied in Salamanca, entered the Franciscan order in about 1520, and came to Mexico in 1529, where he was a professor in the imperial college of Santa Cruz de Tlaltelolco. After thoroughly learning the Aztec language, Sahagun was for more than fifty years a missionary to the natives. His leisure hours were occupied in composing a civil, religious, and natural history of Mexico in twelve volumes, which were illustrated with drawings by the author and copies of the hieroglyphic writings of the Aztecs; but these drawings were considered by the provincial of his order contrary to religion, as perpetuating the idolatrous customs of the natives, and his work was not allowed to be published, but it was sent by the viceroy to the royal chronicler Antonio de Herrera, who used some of the material in his General Historia He died in Mexico, 23 October, 1590. Sahagun's writing were both influential and controversial. At once based on an extensive personal knowledge of Amerindian culture, and driven by missionary zeal to convert the native peoples, he was nonetheless Spanish European and Catholic in his outlook and categorized the native Americans as lazy, inferior and base: either unwilling or unable to hold to Christian teachings and beliefs.

Solis Plate Bataille

larger image 322KBAntonio de Solis, 1610-1673. Histoire de la conqûete du Mexique, ou de la Nouvelle Espagne, par Fernand Cortez / traduite de l'Espagnol de dom Antoine de Solis par l'auteur du Triumvirat Paris, 1774

Spanish dramatist and historian, Antonio de Solis was born in 1610 at Alcala de Henares and studied law at Salamanca , and where he began to pen and produce plays. He became secretary to the count of Oropesa, and in 1654 he was appointed secretary of state as well as private Secretary to Philip IV. Later he obtained the lucrative post of Chronicler of the Indies, (earlier held by Antonio de Herrera) and, on taking orders in 1667, severed his connection with the stage. In his history of the conquest of Mexico Antonio de Solis introduced Hernan Cortez as a modern Alexander the Great with the Aztecs as virtuous Persians. De Solis died in Madrid on the 9th of April 1686.

Solis Plate Grand Temple

larger image 761KBAmerican Exploration

Mollhausen: Zuni New Mexico

larger image 363KBWhat is now the southwest of the United States was essentially unknown territory to the Americans until the Mexican War. The diplomatic crisis with Mexico engendered by the annexation of Texas led the U.S. government to launch a number of “reconnaissance” expeditions toward and along the Mexican border. While nominally and in fact primarily scientific and surveying expeditions they had a clear strategic –purpose as well, to aid in establishing communication and routes and likely military outposts. Finding a traversable overland route (eventually for a transcontinental railroad) to California and its ports lay behind the exploration of the southwest.

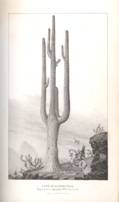

Emory: Cereus Giganteus

larger image 315KBLt. William Emory of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers traveled with General Stephen Kearney's Army of the West as it trekked from St. Louis, to Santa Fe then west to San Diego. This was essentially a military operation which met with little resistance from the Mexican army until it reached California where Kearney 's troops were battered in the Battle of San Pascual. Emory took notes and published in 1848 a report and map of the region which brought for the first time to the American people a scientific awareness of southwestern geography. The Cereus Giganteus , or giant cactus, was described for the first time in Emory's report. The botanical and Indian ethnological notes and from the report were a source of study for decades. Emory carried with him Mitchell's commercial map of Texas, Oregon and California which showed most of the area through which he would march as blank. Emory also was well-read on the antiquities of the Aztec and Inca civilizations in Mexico – he was aware that he was, at times retracing the steps of Coronado. Emory's knowledge of Mexico and the history of the Spanish conquest derived from Alexander von Humboldt's published accounts of his scientific explorations as well as the popular 18th century history of New Spain by James Robertson, who had relied for much of his material on de Herrera's history. It would be felicitous to imagine Emory carrying a volume of Herrera as he traveled through New Mexico and Arizona (he most certainly carried a copy of Humboldt) but suffice it to know he knew Herrera through a later iteration.

Bartlett: Petahaya

larger image 854KBWhen the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in 1848, ending the Mexican War, the difficult issue of establishing the boundary of the territories ceded to the United States by Mexico remained to be settled. A commission was established to draw that line and again the Corps of Topographical Engineers and William Emory were called on to provide scientific expertise. The commission itself bogged down in internal disputes between the military and civilian members and in the politics of presidential appointments and partisan politics, but the survey proceeded and despite the difficult journeying through inhospitable countryside the line was drawn. John Russell Bartlett, an ambitious man of letters from Rhode Island with powerful political connections, who yearned to explore exotic lands, eventually received as a plum the appointment to replace the original Commissioner to head the Mexican Boundary Commission.

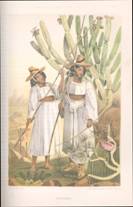

Emory: Papagos

larger image 495KBEmory weathering the various political squabbles in Washington remained as chief astronomer for most of the history of the commission and led the professional and scientific arm of the commission and was responsible for putting together the published report, a massive three-volume compendium of scientific reports, illustrations and maps on the geology, zoology, botany, and ethnography of the region, published between 1857 and 1859. Bartlett published his own two-volume Personal Narrative of the explorations and incidents in Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora, and Chihuahua: connected with the United States and Mexican Boundary Commission, during the years 1850, '51, 152, and '53 in 1854, an engaging travel account, and although of little use to scientists it stands as one of the classics of narrative writing about the American west and the earliest truly popular accounts of the new southwest territories.

Mollhausen: Sandstone

larger image 570KBOne of purposes of Emory's initial reconnaissance of the Mexican borderlands was to identify a possible route for a southern route for a transcontinental railroad. After the territories through which the railroad was to run was safely in American hands, the U.S. government sent out an official survey expedition under Lieutenant Weeks Whipple to explore and map that route which Emory had tentatively sketched out in 1847. The official report and mapping of that expedition comprises volume three of the massive and magisterial report of the Pacific Railway Survey, published between 1855 and 1860. Baldwin Möllhausen, artist, diarist, and writer of Western tales for German audiences and explorer accompanied the expedition and published his two-volume diary, A Journey of a journey from the Mississippi to the coasts of the Pacific with a United States government Expedition in 1858. Mollhausen illustrated his journal with a series of well-executed sketches and drawings. Mollhausen was later asked by Lieut. Joseph Ives to serve as the official artist and collector of natural history for his expedition down the Colorado River, for which Mollhausen painted some of the earliest renderings of the Grand Canyon. Mapping the southwest

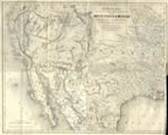

Vivien, 1826

larger image 592KBTwo maps from European atlases delineating the boundary between Mexico and the United States, illustrate the lack of detailed knowledge of the southwest before the Mexican War. A French map published in 1826 by L. Vivien, and a German map published in Stieler's Hand-Atlas in 1828, show the current state of cartographic knowledge exemplified by Henry Tanner's New American Atlas of 1822 and Map of the United States of Mexico of 1825, and Jose Narvaes' 1823 map of New Mexico, Sonora and the California's but these maps still show a number of apocryphal rivers and lakes in the west.

Stieler, 1828

larger image 908KB

Hall, 1836

larger image 651KBA British map of 1836 by Sidney Hall, was based on this map-maker's earlier maps of 1828, provides more topographical detail but still depicts mythical rivers in the west. The boundary between Mexico and the United States was established by a treaty between the U.S. and Spain in 1819 but when Mexico achieved it's independence from Spain, Mexico was reluctant to recognize that line and did not ratify the boundary until 1832 although the line was not surveyed until 1840. Texas declared it's independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836, a political development obviously not reflected in this map. While showing a territory of Texas the map still shows a boundary in Texas between the earlier Mexican provinces of Potosi (named Texas on the 1828 map above) and Cohahuila.

Lapie, 1842

larger image 574KBTwo maps from 1842: a French map of the United States of Mexico by M. Lapie and his son, showing an incorrect southern boundary for Texas, and a more accurate British map published by Chapman and Hall for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge borrowing from Arrowsmith's celebrated Atlas. A boundary commission had drawn the boundary between The Republic of Texas and the United States in 1840. These maps recognize the independent Texas Republic later annexed by the U.S. in 1845.

Chapman &Hall, 1842

larger image 780KB

Bartlett/Colton 1854

larger image 854KBThe map from John Russell Bartlett's Personal narrative, 1854 by J.H. Colton. This map was published before Emory had completed the boundary survey and published the official map of the Boundary Commission in 1857. Colton was one of the most prominent American commercial map and atlas makers. Bartlett 's map shows in much detail current cartographic information about the west, not directly associated with the boundary survey, and does not indicate the final boundary but shows the line that Bartlett had agreed to with the Mexican Commissioner Conde, which was later repudiated by the U.S. Government. The disputed territory was later purchased by the U.S. as the Gadsden Purchase, the boundary of which was surveyed by Emory. Mollhausen/Weller, 1858

larger image 428KBThe map of Baldwin Mollhausen's route from his Diary of a Journey from the Mississippi to the Coasts of the Pacific with a United States Expedition published in London in 1858, executed by British map maker Edward Weller, showing accurately the boundary between Mexico and New Mexico. Home | Introduction | Decades 1 - 4 | Decade 5 - 7 | WDS Home page